第一章 How we make sense of an incredibly complex world 我们如何理解一个极端复杂的世界

Most of the advantages of social life, especially in its more advanced forms which we call “civilization,” rest on the fact that the individual benefits from more knowledge than he is aware of.

Friedrich Hayek (1960). The Constitution of Liberty. In Ronald Hamowy (ed.), The Constitution of Liberty, XVII (Liberty Fund Library, 2011): 73.

社会生活,特别是其更为先进的形式,即我们所说的“文明”的优势,依赖于这样的一个事实,个人受益于比他知道的更多的知识。(《自由宪章》,哈耶克,1960)

***

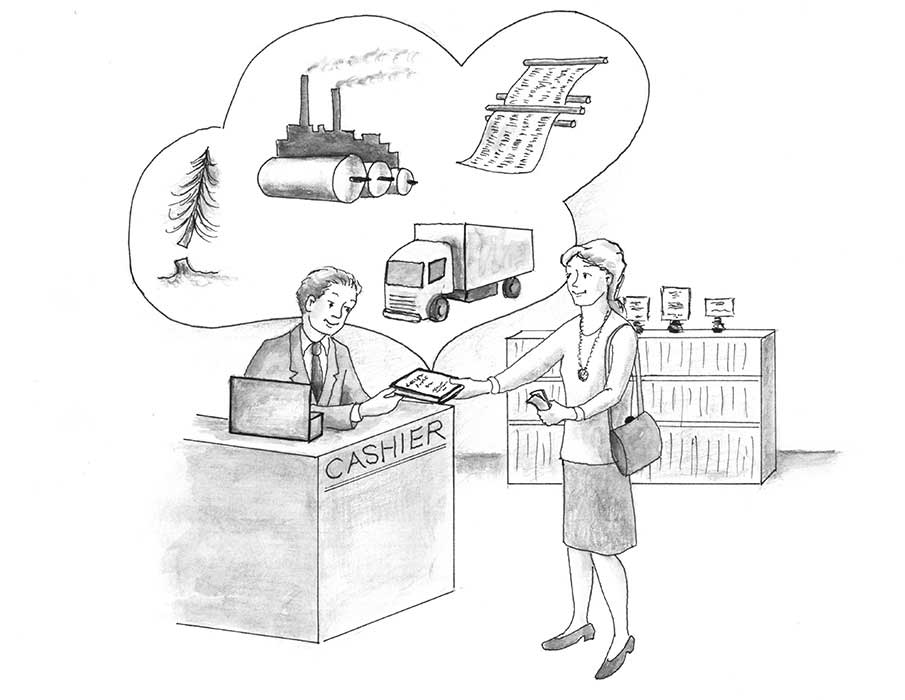

Recent innovations have allowed people to read materials using a wide variety of mediums, including iPads, computers, and even phones. But the original and still most familiar format is paper and ink. Yet the complexity of the coordination required to allow people to read even in this simple format is hard to believe. It illustrates one of Hayek’s most profound insights: the ability of society to organize itself based on the pursuit of individual interests.

最近的创新使得人们可以在多种介质上阅读,包括平板,电脑,以及手机。但是最初的以及最常见的形式则是纸张和油墨。然而,即使是使得人们能够在这种原始的介质上阅读所需要做的协调工作的复杂性也是令人难以置信的。这阐明了哈耶克最为深刻的洞见之一,通过个人对自己的利益的追求,社会将自身组织了起来。

You are now reading words that, for many of you, are transmitted through the medium of two of society’s most familiar products: paper and ink. These products are so common that we take them for granted; their existence seems to be as natural a part of our daily reality as does the force of gravity. And ink and paper are so inexpensive that they are often available free of charge. (When your mail arrives today, it will likely contain several catalogs and flyers advertising this clothing store or that supermarket. The cost of printing these mailings is so low that merchants daily send them out by the jumbo-jet load, all free of charge to those of us who receive them.)

对于你们中的许多人来说,你们现在正在阅读的这些文字,是通过这个社会最为常见的两种产品,纸张和油墨,呈现给你们的。这些产品是如此的常见,以至于我们把它们当成了理所当然的。它们的存在,成为了我们的日常生活中像引力一样自然的一部分。而且纸张和油墨是如此的便宜,它们经常是免费的。(你今天收到的邮件中很可能会包含一些商品目录以及传单,用以宣传这家服装店或者那家超市。印制这些邮件的成本是如此之低,商人们每天都会通过喷气式飞机来寄出它们,而对于收到这些东西的我们来说,则完全是免费的。)

And yet the people whose efforts, skills, and specialized knowledge, and the detailed information that went into producing the very ink and paper now before you, number in the millions. The printed words you are reading were composed by me, the author of this volume. But without the help of millions of other people from around the world, nearly all of whom are total strangers to me and to you, this modest book — the very printed words now before your eyes — would be impossible.

然而,生产现在呈现于你的面前的纸张和油墨却需要数百万人的精力、技能及专业知识,以及不计其数的信息。你正在读的这些文字,是由我,本书的作者写的。但如果没有其他来自世界各地的数百万人的帮助,这本呈现在你面前的小书是不可能完成的,而这些人对于你我来说,都是彻头彻尾的陌生人。

Consider the ink. Where does it come from? Its colour comes from a dye made from chemicals that were extracted from roots, berries, or bark. Who found those roots, berries, or bark? That person had to know which specific roots, berries, or bark to find. Most roots, berries, and bark won’t work. And just how are the colouring chemicals extracted from this vegetation? Today that extraction is done through a complex process involving a mix of industrial chemicals and complicated machinery. The dye is then mixed with water, resins, polymers, stabilizers, and preservatives.

考虑一下油墨,它是怎么来的?它的色彩来自于一种染料,这种染料是用从植物的根、果实、树皮中提取的化学物质制作的。谁找到的这些根、果实、树皮?那个人得知道是哪种根、果实、树皮。大部分根、果实、树皮是不能用的。这种化学物质是怎样从这种植物中提取出来的?这一提取过程需要一个复杂的程序,要用到工业上的化学物质和复杂的机械装置。染料还要和水、树脂、聚合物、稳定剂以及防腐剂混合起来,才能得到油墨。

To make even one vial of the simplest and least-expensive modern ink requires the knowledge and efforts of many, many people. There are those who find the appropriate vegetation, those who design the machines for extracting the colourings, others who operate those machines, and another group of people who mix the extracted chemicals with the other ingredients in order to make the resulting liquid work well as ink. And these steps are only the beginning.

即使制作一小瓶最简单、最便宜的现代油墨也需要非常非常多的人的知识和精力,得有人找到合适的植物,得有人设计提取化学物质的机器,得有人来操作这些机器,还得有人把染料和其他成分混合起来好制成能用的油墨,而这才仅仅是开始。

The machines used to extract the colourings from the roots, berries, or tree bark are powered by electricity. So we need knowledgeable electricians to equip factories with electrical wiring. Other specialists are required to design the electrical-generating equipment that sends electricity coursing through the factories’ wires. In addition to each of these specialists, others must manufacture the wires themselves, a process that involves yet different specialists to find and mine copper, iron ore, and bauxite. And then even other specialists are necessary to perform each of the many steps involved in transforming these raw minerals into copper, steel, and aluminum wires.

用来从根、果实、树皮中提取化学物质的机器是用电力驱动的。所以得有知识丰富的电力专家给工厂布线,还需要其他的专家设计发电装置给工厂供电。除了这些专家之外,还得有人生产电线,而这又需要专家来勘探及开采铜矿、铁矿以及铝土矿,而将这些原料制成铜质、钢质以及铝制的电线所需要的每一个步骤又都需要更多的专家。

And I’ve so far discussed only the ink. What of the paper? What kinds of trees are used to make it? Where are these trees found? Although neither you nor I know the answers to these questions, someone must know. Whoever those specialists are, they are essential to the existence of the printed page now before you.

而我才只是讨论了油墨,那么纸张呢?要用什么树来做纸张?哪里能找到这些树?你和我都不知道这些问题的答案,不过肯定有人知道。不管这些专家是谁,他们对于你面前的这张印满了字的纸张的存在都是必要的。

In addition to those particular specialists, though, the production of paper requires countless other specialists — ones who know how to make the blades for the chainsaws used to cut down the trees; ones who know how to explore for the oil used to make the fuel that powers those chainsaws; ones who know what chemicals, and in just what proportions, must be mixed with the wood pulp in order to transform that pulp into paper; ones who know how to arrange for insurance on the factory in order to make the operation of that factory economically feasible; ones who know how to design, and others who know how to operate, the machines that package the paper for shipment to the printer’s workplace. This list of different people each with specialized knowledge and information goes on and on and on.

除了上面说到的这些专家之外,纸张的生产还需要不计其数的其他的专家,知道如何制作用来砍树的链锯的刀片的专家,知道如何勘探用来生产链锯燃料所需要的石油的专家,知道将什么化学物质,以何种比例掺入木浆,从而将木浆变为纸张的专家,知道如何安排工厂的保险,从而使得工厂的运作在经济上可行的专家,知道如何设计以及知道如何操作用来打包纸张的机器的专家,从而将纸张送到打印工的车间。这个拥有不同的专业知识和信息的人的列表还可以一直罗列下去。

No single person knows more than a tiny fraction of all that there is to know about how to make the ink and paper that you are now reading. What’s more, no single person — indeed, not even a committee of geniuses — could possibly know more than a tiny fraction of all the details that must be known to produce the ink and paper that you now hold in your hands. The details that must be attended to in order to produce these products are truly so vast and complex as to be beyond human comprehension.

关于如何制作你现在正在阅读的纸张和油墨,任何一个人都只了解非常小的一部分,更重要的是,任何一个人,甚至任何一个由天才们所组成的委员会,都只可能了解生产现在你正拿在手中的纸张和油墨所需要的信息的非常小的一部分。为了生产这些产品所需要的信息是如此的广阔及复杂,超出了人类的理解。

And yet, here they are — you’re staring at them at this very moment: ink and paper.

然而,它们现在就在这里,就在此刻,你正在盯着它们,纸张和油墨。

These goods exist not because some great and ingenious human plan called them into being. Instead, they exist because of a social institution that encourages people to specialize in learning different skills, as well as to learn different slices of knowledge and gather different bits of information about the real world. This social institution also sends out signals to these hundreds of millions of specialist producers, informing each of them how best to use his or her special skills and knowledge so that the resulting outputs of the economy will satisfy genuine consumer demands — and do so at costs that are as low as possible.

这些商品之所以存在,不是因为某些伟大而机智的人类的计划使得它们得以实现。相反,它们之所以存在,是因为有这么一种社会制度,激励人们去专门学习不同的技能,了解不同的知识,收集关于真实世界的不同的信息。这种社会制度还给数以亿记的专业化的生产者发出信号,通知他们如何最好的使用他们的技能和知识,从而使得经济的产出能够以尽可能低的价格满足消费者的需要。

If these signals are reasonably accurate, the loggers’ activities are coordinated well with those of the paper mill: neither too few nor too many trees are cut down. And the paper-mill’s activities are coordinated well with those of the printer: neither too little nor too much paper of the sort that you hold in your hands now is produced. Reasonably accurate signals also bring about coordination of the activities of book publishers and the reading public: the larger the audience for a particular book, the larger will be the numbers of that book that are printed. Books that have too small a likely audience to justify the use of paper and ink to produce will remain unproduced by commercial printers.

如果这些信号较为准确的话,伐木工人们的活动和造纸厂的活动就可以很好的协调起来,恰好有那么多树被砍倒,即不多也不少。造纸厂的活动也可以和印刷厂的活动很好的协调起来,恰好有那么多纸被生产出来,即不多也不少。较为准确的信号也把书商的活动和公众的阅读需求协调起来,对于某本书,读者越多,书的印数也就越多,读者过少的书籍,则不值得耗费纸张和油墨,不会被商业印刷厂生产。

Through these signals, therefore, millions of producers all across the globe — business firms, entrepreneurs, investors, workers — are guided to act in ways that “mesh” productively with each other. We get affordable ink and paper — and also automobiles and laptop computers and antibiotics and sturdy housing and supermarkets full of food and department stores full of clothing. The list is very long indeed.

因此,通过这些信号,遍布全球的数以百万计的生产者们(企业、企业家、投资者、工人)的行动被颇有成效的啮合在一起。而我们则得到了可以负担得起的纸张和油墨,以及汽车、笔记本电脑、抗生素、坚固的房屋、满是食物的超市、满是衣服的百货商店,这个单子还可以一直列下去。

One of the most notable facts of life in modern market economies is that each and every one of the things that we enjoy as consumers is something that no person knows in full how to produce. This fact is true, of course, for marvels such as smart phones and transoceanic jet travel, but it’s no less true for mundane items such as ink and paper. The production of each and every one of these things requires the knowledge of thousands or millions or even hundreds of millions of people. Yet there is no overarching plan to make all these activities come together productively.

现代市场经济的生活中最值得注意的一个事实是,我们作为消费者所享受的任何东西,其生产所需要的知识,都是没有人能够完全了解的。这个事实对于像智能手机和越洋航行的喷气式飞机这样的技术上的奇迹来说当然是真的,但对于纸张和油墨这样的日常的产品也是如此。生产这些东西需要数以千计、或者数以百万计乃至数以亿计的人的知识。然而,并没有什么包罗万象的计划使得这些活动有成效的结合起来。

Of course, each individual worker plans and consciously guides his or her actions. Each individual firm plans and manages its activities. There is conscious planning and adjustment going on at the level of each individual and each firm and each distinct organization. But there is no overarching—no “central”—plan for the whole. No conscious, central plan or blueprint knits each of the millions upon millions of individual choices, actions, plans, and slices of knowledge into the larger outcome of “the economy.” That larger outcome is, as F.A. Hayek described it, spontaneously ordered.

当然,每个工人都会进行计划,有意识的以此指导他或她的行动。每家公司也都会进行计划,管理它的活动。在个体、公司以及组织的层面上,都有着有意识的计划和调整。但对于整体来说,并没有包罗万象的或者中央的计划。并没有什么有意识的中央计划或者蓝图将成千上万人的选择、行动、计划,以及他们所拥有的知识整合起来,形成更进一步的结果,即“经济”。“经济”,如哈耶克所说的,是自发生成的。

But how? What exactly is this social institution that coordinates the choices and actions of so many people, each with different slices of knowledge and information, into an overall pattern of activities that works so remarkably well? The answer is voluntary exchange, or markets that are based on private property rights and freedom of contract. That is, for individuals to be able to exchange in markets (sell and buy) they must feel confident in the security both of their own property and that of those they exchange with, as well as in the legal system (contracts) within which they operate. And the prices that emerge on these markets through thousands, even millions of exchanges, are the crucial signals that guide us every day to make those economic choices that result in the complex and highly productive economy that we too often take for granted. Market prices, as we’ll see in the next section, guide each of us to act as if we know about—and as if we care about—the preferences and well-being of millions of strangers.

但是这是怎样实现的呢?到底是什么社会制度将如此多的人(每个人都有着不同的知识和信息)的选择及行动协调起来,使之形成这一运转如此之良好的活动的模式呢?答案是自愿交换,或者说基于私有财产权利及契约自由的市场。也就是说,对于个人,他们要想能够在市场上交易,即买与卖,他们必须对他们自己的以及他们所要交易的财产的安全有信心,也要对他们于其中行事的法律系统或者说契约有信心。而在这些市场上,经由数千次乃至数百万次的交易所形成的价格,则成为了指导我们每天的经济决策的至关重要的信号,并进而形成了这一我们经常认为是理所当然的但却是复杂而富有成效的经济。而市场价格,正如我们将在下一节中所看到的,指引着我们,使得我们以仿佛了解甚至在乎数以百万计的陌生人的偏好及福祉的方式行动。